Kabineh: The Syrian Town That Helped Save the Revolution

The road to Kabineh is long and winding. The exit to the town approaches rapidly as you travel along the M4 highway, with no signs marking it. Upon exiting, a tiny, potholed path quickly splits into a half dozen different directions, each junction narrower and more unused than the last.

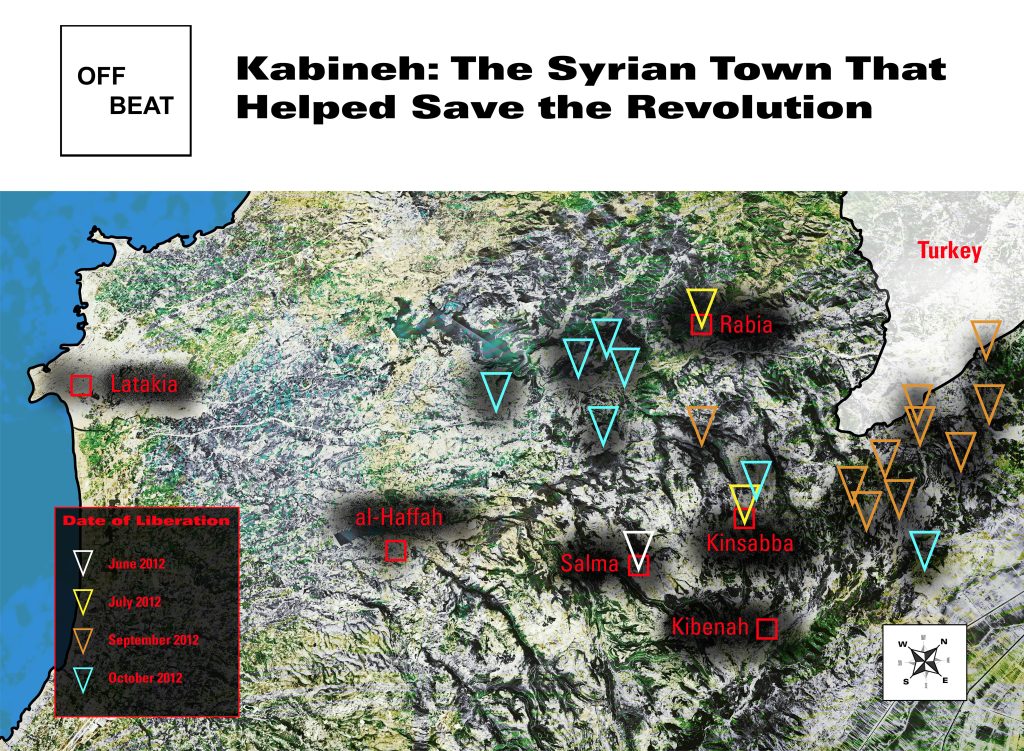

This spiderweb of roads blankets the Jabal al-Akrad mountains in Syria’s northern Latakia province, where olive groves have been carved into the sides of steep ravines, marking what for 14 years had been the eastern wall of the Assad regime’s heartland. Tucked away in this rugged land are more than 50 villages, all empty and destroyed.

Kabineh had once been the heart of the revolution in Jabal al-Akrad. In later years, it gained fame as the unbreakable outpost of the country’s last revolutionaries, withstanding a nine-month assault by thousands of soldiers, artillery, jets, and helicopters. The small village, which sits on the highest and easternmost point of Jabal al-Akrad, has always been a strategic military position connecting the rolling hills of the Idlib governorate with the coastal mountains of Latakia.

But long before the battles that brought it international fame, Kabineh had already become the center of Jabal al-Akrad’s revolution.

A small demonstration in Kibenah in July 2012.

Abu Ahmed Issa sits with his back to a cracked and scarred concrete wall, on a floor littered with rubble and the torn fabric of what once might have been a couch or bed. Light pours in from the two absent walls of the house. We are in the center of Kabineh, overlooking the barren apple field in the plateau to the north. An occasional truck or motorcycle slowly drives along the dirt road outside, usually filled with broken concrete dug out of the other destroyed homes. At one point a driver stops to say hello; strapped to the back of his bike are the remnants of an old Russian barrel bomb he recovered from his home.

What remains of Kabineh’s homes. // Photo credit: Gregory Waters, Gregory Waters, Nicholas Waters.

Even now, 8 months after the fall of Assad, Kabineh is a ghost town. Every single home has been bombed and shelled hundreds of times. A handful of residents – less than a dozen – have started to visit again, hoping to rebuild a single room so they can finally move their families out of the tent camps along the Turkish border that they have been stuck in for over a decade. There is no electricity, there is no food, and there are no working wells. The only water comes in small tanks in the back of pickup trucks.

Of course, it was not always like this.

From Peaceful Protests to Self-Defense

Abu Ahmed was the founder of the village’s Free Syrian Army group in 2011. Before that, he had helped organize and lead peaceful protests. As he remembers, the first protest the village ever held was a walking tour through the neighboring villages. This was a common method of protest in rural areas, where each village was too small to have their own large gathering. Instead, people would gather in one village and begin traveling along the roads to others, picking up more demonstrators along the way.

For three months, the people of Kabineh hosted weekly demonstrations against the Assad regime. Almost immediately they were faced with raids and attacks from security forces based out of the police center in nearby Kinsabba, the administrative center of the area. Regime patrols would approach Kabineh from Kinsabba via a narrow valley to the south, usually sending dozens of vehicles carrying police and mukhabarat each time.

The long, narrow road into Kabineh from Kinsabba. // Photo credit: Nicholas Waters

The first martyr fell in March. Haroun Wassouf, a teenager from Sirmaniyah village, was in Kabineh with a friend to attend a protest that day, but the two boys were caught in a regime raid. Haroun was killed by security forces, and his friend was detained and never seen again.

Abu Ahmed explains Kabineh’s reaction to the non-stop attacks with a phrase heard across every opposition community in Syria: “We decided to move from a peaceful revolution to a military revolution.” On 1 June 2011, the Assad regime fully militarized their counter-revolution crackdown in the northwest. Thousands of soldiers were deployed to Idlib and rural Latakia governorate. Columns of tanks, artillery, and armored vehicles entered towns across the countryside, setting up checkpoints and bases along the M4 highway and reinforcing the Turkish border. A few days later, Colonel Hussein Harmoush announced his defection from the regime and the creation of the Free Officers Movement in rural Idlib, a new armed entity which would defend communities from regime attacks.

It was in this context that the men of Kabineh took up weapons for the first time. That summer and fall they simply served as a local defense force, using their hunting rifles and small arms to defend the ongoing demonstrations in their village. This was enough to end the raids, but regime forces instead set up positions across the valley, and resorted to targeting the village randomly. In December, Abu Ahmed organized the village’s men into its first proper opposition group, “Katiba Umm Al Thuwar,” and announced their allegiance with the defected colonel Riad al-Asaad’s Free Syrian Army (FSA).

Forming an armed faction in these early months was no small matter. Taking up arms meant sacrificing work and the freedom to travel, losing precious income for your family. Townspeople often came together to support the men who joined the local armed faction with donations and food. Kabineh was no exception. One woman, Umm Ahmed, soon became known as Umm Al Thuwar, “Mother of the Revolutionaries”, for her endless care and support for all of the fighters who stayed in the village. “She fed us, she cleaned our clothes, she looked after us and cared for us,” recalls Ahmed Issa, Abu Ahmed’s son. Other fighters describe how she served as a nurse for wounded men and consoled them after they lost brothers in battle. There was no question about naming Kabineh’s armed group in her honor.

Umm Al Thuwar with Lt. Colonel Muhammad Hamdou, circa 2012.

Throughout the latter half of 2011 and 2012, Kabineh would become a hub for revolutionary activity and a sanctuary from the regime. Whenever someone defected in the Latakia region, rebel networks would first bring them to Kabineh where they could decide to leave for Turkey or join an armed faction. Civilians also sought refuge from regime raids – and later the indiscriminate shellings and airstrikes that would flatten every village in the mountains. According to Abu Ahmed, by 2012 even Christian families from Ghanem and Kinsabba were fleeing to Kabineh.

In early 2012, armed factions started to form rapidly across northwest Syria. Initial coordination between these hundreds of local groups was poor at best, and so many began to merge into more coherent structures. In February, a small group of defected and retired regime officers from Latakia city arrived in Kabineh, led by retired lieutenant colonel Muhammad Hamdou. In March, The men joined the small group in Kabineh and together formed a plan to ignite protests across Jabal al-Akrad. At each protest, this small FSA group stood in defense, and each time they would gain a few new recruits from that village.

The pattern continued until late March 2012, when a large regime convoy stormed Kabineh to put an end to the instigators. The group was too small to repel the attack. Everyone fled into the woods, while regime forces slaughtered every animal and ransacked the homes. The attack finally brought the mountain to the attention of the revolutionary groups elsewhere in the northwest. Weapons and recruits began to flow in.

Armed with just a few rifles and mines, the small group of fighters attempt to repel the regime advance on Kibenah on 23 March 2012.

Kabineh on the Attack

Over the next two months, Kabineh became the hub of a rapidly growing coastal armed group. By late May more than 250 fighters had gathered in the village and, in a video filmed on the plateau north of Kabineh, formally announced the formation of Liwa Ahrar al-Sahel under the command of Hamdou.

Video announcing the formation of Liwa Ahrar al-Sahel.

The group quickly went on the offensive. On 25 May 2012, a group of fighters from several component battalions stormed the Kinsabba Police Center, which had been the heart of the regime’s raids and detentions in the area. The men, armed only with rifles, were able to seize the center after a few hours of fighting while another unit successfully ambushed initial regime reinforcements near the M4 highway. However, according to regime media at the time, the ambush on the police reinforcements triggered a larger mobilization of special forces units stationed along the M4, who then moved to Kinsabba and raided nearby villages, forcing the opposition fighters back north.

Video showing members of Liwa Ahrar al-Sahel breaking into the Kinsabba Police Center.

Yet Hamdou had always intended to withdraw his men from Kinsabba. Not only had reinforcements been sent from the two main military bases on the M4, they had also been deployed from Salma, a strategic town south of Kinsabba which sits on the main road connecting the Hama plains with Jabal al-Akrad.

“Everyone asked me why I would liberate it and then withdraw,” Hamdou explains to me in a cafe along the Latakia shoreline on a cool November evening, “but it was part of the military plan and I couldn’t tell them; It was to open the Salma front.”

Ten days later, 100 men from Liwa Ahrar al-Sahel, mostly consisting of Salma locals, infiltrated the town in civilian clothes. Other units prepared to cut the roads in and out of the town. The attack began around 7 PM, targeting the now reduced garrisons in Salma’s Military Intelligence HQ, Political Intelligence HQ, and police center. On the morning of 5 June 2012, Liwa Ahrar al-Sahel announced the capture of the town.

That same day, local fighters in Haffeh, 8 miles to the southwest, launched their own operation to fully liberate their city, whose police center was still held by regime forces. Despite initially capturing the positions, the regime soon deployed significant military reinforcements, as well as helicopter gunships, besieging Haffeh for several days.

The Jabal al-Akrad fighters quickly moved south, opening a path to Haffeh to help evacuate those local fighters and families. As the regime recaptured the town, these groups pulled back north. Some of the Haffeh fighters then integrated into Liwa Ahrar al-Sahel, while others continued on to Turkey.

Despite the devastating loss of Haffeh, Abu Ahmed recalls that the successful evacuation of the fighters boosted the overall morale of the factions and honed their determination to liberate the mountains. Their focus now turned north and west, eyeing the international highway connecting Latakia with Idlib and Aleppo. The M4 was being held via a series of checkpoints and bases located out of several large towns, with Bidama and Zaaniyah the two closest to Kabineh. As long as the regime maintained these positions, it would be able to exert heavy pressure on any serious opposition advances in the area.

In late July, the ever-growing Liwa Ahrar al-Sahel went on the offensive again. Several battalions in Jabal Turkmen united to liberate the strategic town of Rabia in a battle which only lasted a few hours. A few days later, battalions based in Jabal al-Akrad returned to Kinsabba, this time capturing the police center for good.

The first serious crack in the regime’s defenses, however, came on 3 September 2012, when a small group of opposition fighters stormed the regime’s base on Burj Qassab. The mountaintop sits on the western side of a large valley separating Salma and Jabal al-Akrad from Jabal Turkmen, overlooking much of Jabal Turkmen and Jabal al-Akrad. Regime forces had established a reconnaissance and artillery base here, which they used to shell Salma and other liberated areas and to monitor the opposition’s movements in the region.

The capture of Burj Qassab opened the door for the first real multi-axis offensive in Latakia. Three weeks later, all the component factions of Liwa Ahrar al-Sahel launched a coordinated assault on regime positions in both Jabal Turkmen and Jabal al-Akrad. More than six villages were seized along the Rabia-Burj Qassab axis, reaching all the way to the edge of the coastal plains. To the east, several villages near Kinsabba and Jisr ash-Shoughur were also liberated.

Regime forces were now nearly cut off in a large pocket along the M4 highway between Salma and Jisr ash-Shoughur, and the rebels of Jabal al-Akrad finally had opportunity to eliminate the threat to their villages. Opposition units operating in Idlib now joined those fighters in Latakia to launch an assault on the regime’s heavily fortified bases along the M4 and the Turkish border.

Throughout the first week of October 2012, opposition factions launched assaults on the regime’s core bases in Bidama and Zaaniyah, which together housed two battalions of the 35th Special Forces Regiment. Dozens of soldiers were killed and more than 200 POWs were captured. The liberation of these two towns and their surrounding checkpoints resulted in the seizure of multiple armored vehicles, heavy mortars and field artillery, and hundreds of light arms. Further north, the Idlib factions swept through remote mountain villages along the Turkish border, expanding the quickly growing safe zone along the border. By 8 October, the M4 had been secured from Salma to Zaaniyah, cutting off the regime’s forces in Idlib from Latakia.

The Heart of Free Latakia

What had just months earlier been an archipelago of liberated towns in a sea of regime checkpoints was now one broad swath of free Syria. Over the ensuing years, a series of opposition and regime operations would push this frontline east and west; for one brief moment in 2014, rebels were able to reach the Mediterranean Sea. But gradually, regime forces, backed by Russian ground and air units and Iraqi foreign fighters, were able to push back the frontlines and reclaim key towns like Rabia, Salma, and eventually Kinsabba.

Throughout all of this, regime and Russian jets and artillery pounded Jabal al-Akrad. All 52 villages were depopulated, and any building still standing was targeted. Even as regime forces advanced northward, Kabineh remained steadfast. Its houses flattened, the defenders moved into caves and tunnels carved deep under the mountain tops. At one point in the war all of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham’s leaders based themselves nearby, using the mountains to protect themselves from Russian airstrikes.

Fighters from Hayat Tahrir al-Sham posing in the tunnels beneath Kabineh, November 2019.

Kabineh would face several regime assaults in the later years of the revolution, but none as prolonged and intense as it faced during the regime’s final attempt to seize the village. From May 2019 until February 2020, regime, Russian, and Iranian forces launched wave after wave of infantry assaults on Kabineh and its adjacent hilltop. Helicopters and jets dropped barrel bombs and bunker busters on the area, and the infamous 4th Division fired hundreds of rockets, including some filled with chlorine, at the village’s defenders. Kabineh never fell, even as the regime swept through northern Hama and southern Idlib. Had the regime been able capture Kabineh, it would have likely swept through western Idlib, potentially crushing the remaining opposition fighters before the February ceasefire had a chance to freeze the frontlines.

Returning Home

The history of Syria’s revolution cannot be written without Kabineh. From the first liberations in northern Latakia to ensuring the opposition had the space in Idlib to prepare and plan the final 2024 offensive, Kabineh was in the center of it all. But when the Assad regime collapsed on 8 December, there was no one left in the village to celebrate. Kabineh’s residents had long been thrown to the wind: disappeared in Assad’s prisons, martyred in the demonstrations and battles, forced as refugees abroad, or living in tents in Idlib.

A police officer, a local from Jabal al-Akrad, walks up Kabineh’s main road. // Photo credit: Nicholas Waters

Even 8 months after liberation, almost no one had returned to Jabal al-Akrad. Only those with partially fixable houses had begun the long journey back to the mountains. A few men from these families sleep under tarps strung between broken walls as they rebuild, brick by brick, a single room in an otherwise uninhabitable house. In Kinsabba, a few Christian families have begun to return – new roof tiles can be seen along their houses and the town’s church, which had been destroyed by regime jets.

Others who owned farmland have returned to try and work the fields, even if it is too late in the season to plant anything. One such man sleeps on an elevated platform of thin branches he has built along the road to Kabineh, tending to a small, newly cultivated patch of dirt. The plateau north of the village used to be a large apple orchard; now it is a dry, grassy field with almost every tree cut or burned down.

The plateau north of Kabineh where Liwa Ahrar al-Sahel was announced, now bereft of its orchard. // Photo credit: Gregory Waters

The struggles of Kabineh’s inhabitants are not unique for many Sunni communities across northwest Syria. Most towns in northern Hama and southern Idlib, and entire neighborhoods in Homs, had likewise been flattened and depopulated by regime forces. But the remoteness of Jabal al-Akrad and the small size of its villages has left these communities with few outside resources to support their reconstruction and has made it difficult for humanitarian organizations to supply them with basic goods. Despite the storied history of this region’s revolutionaries, their battle is not yet over.