Revisiting Jammu & Kashmir Six Years After the Revocation of Article 370

I. A Monumental Constitutional Change and Its Contested Justifications

OP-ED: The state of Jammu and Kashmir has undergone many historical events, from the creation of Pakistan and India to the discussion of its political status at the United Nations. This includes four wars between India and Pakistan over the territorial claim, and the rigged elections of 1987 leading to sustained armed insurgency and counter-insurgency for the next 30 years.

On August 5, 2019, the Indian government executed a monumental constitutional change through presidential order, revoking the Article 370 and 35a that had granted Jammu and Kashmir the power to formulate its own constitution and legislate on all matters except defense, foreign affairs, and communications (International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, Mar 2024, 5(3), pp. 1166-1168). The constitutional change, designated the ‘Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act’, bifurcated the state into two Union Territories, a move intended to centralize governance and accelerate integration of Jammu and Kashmir into the Indian government’s primary administrative structures.The state was bifurcated into the Union Territory (UT) of Jammu and Kashmir, to be directly controlled from the national capital, and Ladakh was severed to become another UT.

This is considered a watershed moment in the political history of Jammu and Kashmir. While the party in power in Delhi (BJP) decided the revocation of Article 370, Kashmir’s population was put under an unprecedented curfew. Most Kashmiri political leaders were detained, so no voice was raised, and there was no consultation with the people’s representatives of J&K.

The central Indian government’s justification for revocation was predicated on the premise that Article 370 had infested anti-state feelings in J&K, plunging the region into an economic disparity that helped adversaries (like Pakistan) manipulate the common masses. The Indian government claimed this move would thus foster socioeconomic development and establish legal uniformity. Proponents of Article 370’s revocation argued that dissolving unique legal barriers like special status of the erstwhile state would eliminate obstacles to investment, grant unparalleled access to national markets, and foster a more favourable climate for enterprises. (IJRPR, Mar 2024, 5(3), pp. 1166-1168).

Conversely, significant scholarly analysis highlights profound sociopolitical and constitutional ramifications. The implementation of Article 370’s revocation — characterized by a stringent security clampdown, communications embargoes, and the widespread detention of political figures — has been intensely scrutinized. Critics contend the abrogation of Jammu and Kashmir’s status was undertaken unilaterally and arbitrarily, without the consent of the Jammu and Kashmir Constituent Assembly, raising fundamental questions concerning democratic practice and federal principles (IJRPR, Mar 2024, 5(3), pp. 1166-1168). Empirical research indicates severe psychosocial impacts, including heightened identity crises and mental stress, with the local population perceiving the act as widening the rift with the Indian government (IJRPR, Mar 2024, 5(3), pp. 1166-1168). Furthermore, concerns persist regarding the erosion of the region’s demographic character and a precarious human rights situation under a heightened security paradigm (IJRPR, Mar 2024, 5(3), pp. 1166-1168).

Six years later, the promises of peace and prosperity are being tested by economic strain, persistent security challenges, and delayed political restoration. This report examines key parameters over the past six years to evaluate the impact of India’s most significant constitutional and political reorganization in recent history.

II. Macroeconomic Reversal: Stagnating Investment and a Deteriorating Fiscal Position

Economically, the outcomes of the reforms remain complex and contested. An analysis of macroeconomic data indicates a pronounced economic reversal in Jammu and Kashmir following the abrogation of its special constitutional status under Article 370 in 2019. When compared to the preceding five years (2014 – 2019), key indicators of investment and fiscal health have deteriorated significantly, suggesting a challenging transition to its new status as a Union Territory (RBI, 2023a).

A Kashmiri fruit-seller displays a variety of fruit, including bananas, kiwis, and apples. // Photo credit: Author

Whereas the regional economy previously demonstrated a degree of stability amidst longstanding challenges, the post-2019 period has been characterized by a severe contraction in capital investment. Gross Fixed Capital Formation , a critical indicator of productive capacity expansion, declined by approximately 50% between the 2016-17 and 2022-23 fiscal years (J&K DES, 2023). This stagnation is further evidenced by a significant implementation gap in investment commitments. Despite announcements of investment proposals totalling ₹2.15 trillion (approx. $25.8 billion) in 2023, the actual materialized investment was a mere ₹25.18 billion (approx. $302 million), indicating a fulfillment rate of just over 1% and a performance markedly weaker than historical trends (Chowdhury, 2024).

Concurrently, the region’s fiscal sustainability has come under considerable strain. The internal debt burden of the Union Territory doubled in the five years following the abrogation of Article 370 (RBI, 2023b). Consequently, outstanding liabilities have surged to approximately 60% of the Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP)—a figure that is nearly double the national average and represents a significant increase from pre-2019 levels (RBI, 2023b). While the tax-to-GDP ratio increased from 6.3% to 8.4%, a change largely attributable to the integration into the national Goods and Services Tax (GST) regime, these revenue gains have been effectively neutralized by rising expenditures. As a result, the fiscal deficit has persistently remained above the targets stipulated by the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act (GoI, 2024).

Furthermore, trends in the financial sector point towards underlying structural weaknesses. Although the credit-deposit (C-D) ratio has shown improvement, analysis suggests this growth is not fuelled by productive industrial credit but rather by consumption-led borrowing (Khan, 2023). This pattern of credit allocation fails to support long-term capital formation and economic expansion, indicating a deeper structural malaise within the Jammu and Kashmir economy that extends beyond surface-level fiscal metrics.

Economist Dr. Haseeb Drabu, in his paper Macroeconomic Performance of Jammu & Kashmir: A Post-2019 Overview, corroborates this analysis: “The economic performance since the 2019 reorganization has not met expectations. [Jammu and Kashmir’s] growth trajectory has reversed, with the compound annual growth rate of its SDP dropping from 10.2% pre-2019 to 8% post-2019, while real income growth plummeted from 7% to under 4%.” He further notes the widening gap in living standards: “While per capita income has grown, its rate has halved since 2019, causing J&K’s income relative to the national average to fall from 84% in 2011-12 to just 76% in 2023-24.”

III. The Human Dimension: Escalating Employment Crisis and Societal Stress

This macroeconomic stagnation translates directly into a severe human crisis of unemployment and economic distress. Studies focusing on educated youth in the Jammu region suggest that economic revival is contingent upon significant growth in local enterprises, substantial investments in industry, infrastructure, and key sectors like tourism and horticulture, and utmost transparency in development planning (IJRPR, 2024, p. 1167). A primary concern is the urgently high unemployment rate, which necessitates the revitalization of ailing industrial units to create sustainable employment opportunities for the youth (IJRPR, Mar 2024, 5(3), pp. 1166-1168).

A clothier is seen stitching a shirt for eventual sale. // Photo credit: Author

A baseline survey for the Jammu and Kashmir Mission YUVA entrepreneurship program for fiscal years 2024-25 provides stark data: Jammu and Kashmir has an unemployment rate of 6.7%, nearly twice the national figure of 3.5% (Government of J&K, 2024). The report shows more severe unemployment among youth (17.4%) and urban females (28.6%), highlighting persistent economic and gender-related challenges. The report shows substantial regional disparities, with the highest unemployment rate at 9.3% in the Rajouri and lowest at 3% in the Samba districts. Dr. Drabu identifies an “employment paradox”: “Despite a significant rise in labour force participation from 56.3% to 64.3%, [Jammu and Kashmir] grapples with a severe jobs crisis, with unemployment spiking to 23.1% in 2023 and remaining at 17% in 2024—more than double the national average.”

While nearly half the working-age are ‘own-account workers’, indicative of a high level of entrepreneurial potential, the report points out poor support infrastructures and restricted access to credit as serious challenges. Mission YUVA aims at creating 137,000 enterprises and creating 425,000 employment opportunities in five years, and addresses those challenges in an economy that has shifted significantly from agrarian to a services sector that contributes 63.57% of the total economic output. Dr. Ejaz Ayoub, an economist, contextualizes this rise in self-employment not as resilience but as compulsion: “The rise in self-employment is largely a compulsion driven by necessity—a survival mechanism due to the lack of adequate formal job opportunities, especially for youth and women.” On addressing the gap, he states: “The gap between plans and jobs stems from insufficient investment and a weak industrial base. To move the needle in two years, we must promote entrepreneurship, boost investment in job-creating sectors, and strengthen labor policies.”

IV. The Mirage of Normalcy: Interrogating Tourism Data and Security Incidents

The Union government frequently points to record tourism figures as the primary evidence of normalization and restored peace. However, a Right to Information (RTI) query filed by M.M.Shuja (Journalist, and Right to Information activist) revealed huge gaps in actual tourism figures for Jammu and Kashmir, therefore calling into question assertions that more tourism equals normalization since Jammu and Kashmir lost its special status in 2019.

A basket-seller is seen manning his stall at the 2025 Kashmir Marathon Expo, an event held annually by the Indian government’s Jammu & Kashmir Department of Tourism. // Photo credit: Author

Differing from the Union government figure of 94.7 million tourists during the years from 2019 through 2024, a perusal of data pulled from the Kashmir Tourism Department, recognizes that only 9.28 million persons—who account for less than 10% of the total—actually visited the Kashmir Valley (Jammu and Kashmir Tourism Department, 2024). A huge bulk of nearly 85 million tourists descended into the Jammu region, including over 43.3 million pilgrims visiting the Mata Vaishno Devi shrine during the corresponding timeframe (Rajya Sabha Parliamentary Committee, 2024).

There are huge discrepancies in yearly numbers. The government’s Economic Survey 2024-25, for instance, stated that there were 3.498 million tourists in 2024, while the Kashmir Tourism Department’s registers indicate 2.986 million—a gap of over 0.5 million tourists (Economic Survey 2024-25; J&K Tourism Department, 2024). The same kind of gaps are seen for the years 2021-2023.

The report questions persistent claims by the central government that high tourism traffic is a proof of post-2019 normalization and integration. The experts note that the conflation of pilgrimage traffic and leisure tourism in the Kashmir valley would unwittingly exaggerate numbers and mask ground realities. The report points out the importance of transparent and disaggregated data compilation for a correct analysis of the socioeconomic situation in the valley. This mirage is further challenged by security realities on the ground. A deadly terror attack in Pahalgam this summer underscored enduring security vulnerabilities, demonstrating that the security situation remains complex and volatile despite official narratives.

Siddiq Wahid, a renowned academic and historian, attributes the alarming rise in youth suicides and drug addiction to profound disillusionment, as the government’s promised plans have failed to materialize into substantive improvements on the ground.

He also demystifies the state’s reliance on tourism statistics as a misleading indicator of prosperity. “Tourism constitutes a mere 7% of the economy, while horticulture and agriculture are the true drivers of Kashmir’s GDP,” he clarifies. “Yet, both of these vital sectors have suffered due to poorly managed government policies and climate change.”

“In contrast,” he argues, “the touted tourism numbers are artificially inflated, as figures from Hindu pilgrimages are disingenuously clubbed with those of commercial leisure travelers. This creates a strategic smokescreen to project a façade of normalcy that obscures a harsh economic reality.”

V. A Fragile Political Restoration and the Paradox of Governance

The restoration of a popular government in Jammu and Kashmir after the abrogation of its special status in 2019 has not restored the earlier political autonomy of the State but has instead solidified a more fragile and restricted political climate. Though electoral processes have resumed, the underlying framework governing the dispersal of power severely weakens the premises of representative democracy. The maintenance of significant ministries, such as police, public order, and services within the purview of the centrally appointed Lieutenant Governor — a constitutive component of the Union Territory (UT) model — creates a persistent fountainhead of institutional tension and practically dilutes the power of the popular government. This structural subservience was vividly illustrated by the furore over the observance of Martyrs’ Day in July 2023, when a significant divide among elected delegates and the UT administration shed light upon the persistent and unresolved tensions regarding symbolic control and administrative power (The Hindu, 2023).

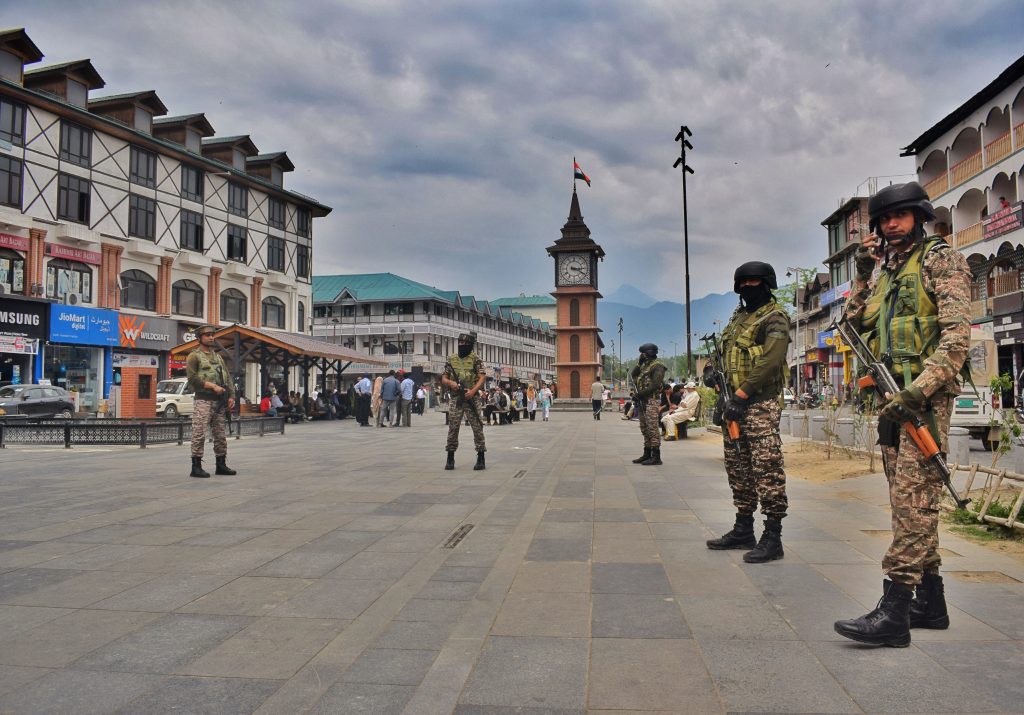

A group of security forces are seen stationed in Lal Chowk Square, Srinagar. // Photo credit: Author

Consequently, regional parties are trapped in a major ideological and practical paradox. Political institutions like the National Conference (NC) and Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), while officially promoting Article 370’s restoration, are compelled into a system of governance that legitimizes its abrogation (Bose, 2021). This situation has bred a political environment that exhibits what academicians term “competitive assimilation,” whereby parties need to balance the tension between their founding ideology and the practical compulsions of existing and working within the new model of altered constitutional structure (Wani & Bhatt, 2022). The new government’s first cabinet resolution that asks for a restoration of statehood provides proof of this tug-of-war politics, openly acknowledging the democratic deficit inherent in the U model (Greater Kashmir, 2024).

This political analysis is extended by Radha Kumar (Indian academic and author who was a part of 3 member interlocutors panel to Jammu & Kashmir), who in a 2023 report titled Jammu and Kashmir: From Political to Economic Dispossession, writes that the 9-year delay in holding legislative assembly elections cannot be justified by security concerns. She points out that elections were successfully conducted in the past during periods of significantly higher violence, such as in 1996 and 2002. Instead, Kumar attributes the delay directly to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) political strategy, contending that after withdrawing from the coalition government in 2018, the BJP administration pursued a policy of “forcible implementation” of its integration agenda. She supports this with data showing a sharp decline in GSDP growth and a rise in unemployment, concluding that the administration has failed even on its own terms, and that elections remain delayed because the majority of residents see them as a “lesser evil” to direct central rule, which has been marked by political purge, economic decline, and administrative dispossession.

Despite enormous administrative investments undertaken at the behest of the central government, such as a 100 billion USD initiative for the restructuring of power transmission for reduction of transmission and power distribution losses, and wider legal reforms such as substitution of the Ranbir Penal Code by the Indian Penal Code, those initiatives are nearly exclusively viewed as top-down measures for integration and normalization (GoI, 2023). The interplay of political marginalization, ideological co-option, and governance predominantly directed from the center has made Jammu and Kashmir’s political condition more fragile and conflictual than the pre-2019 template of statehood that was certainly weak, but which provided a higher level of political agency for those legislatures that have been elected.

VI. Evolving Crime Trends, Societal Correlations, and a Paradox of Reporting

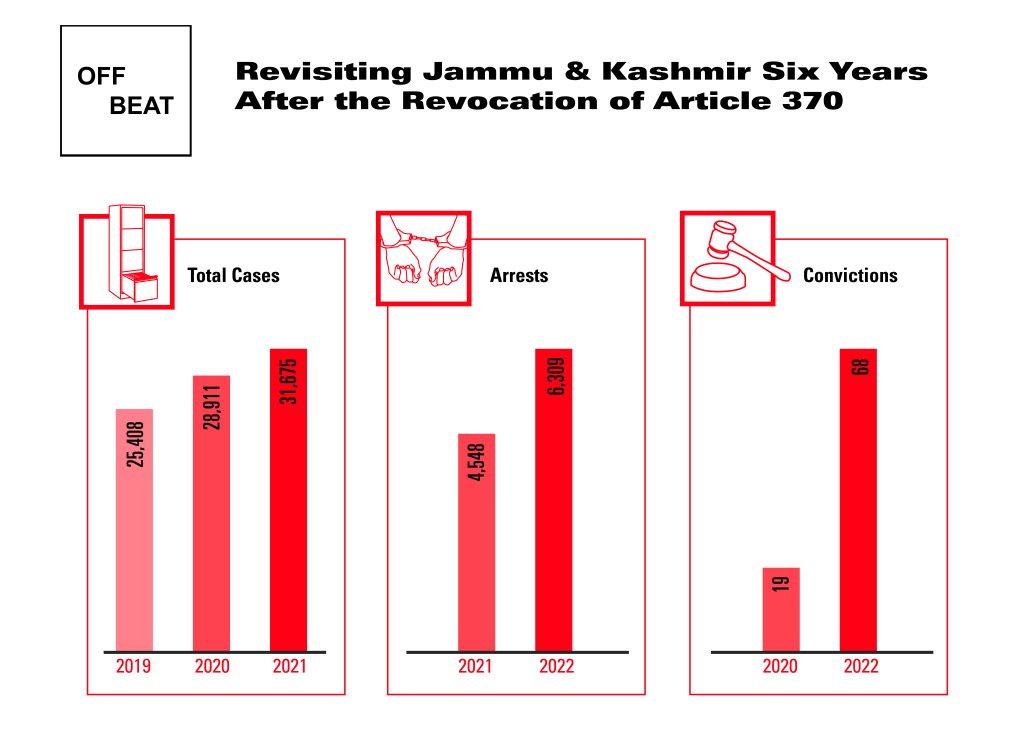

According to records from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), the UT of Jammu and Kashmir has seen a major upward trend in its general crime rate. From 2019 to 2021, registered cases grew by 26.4 percent from 25,408 cases to 31,675 cases, with an intermediate 28,911 cases in 2020. This trend, however, has recently started to indicate regional divergence. Police officials announced a dip in criminal cases in the Jammu region in 2024, which they claim is a result of effective policing strategies, improvement in community relations, and preventive action.

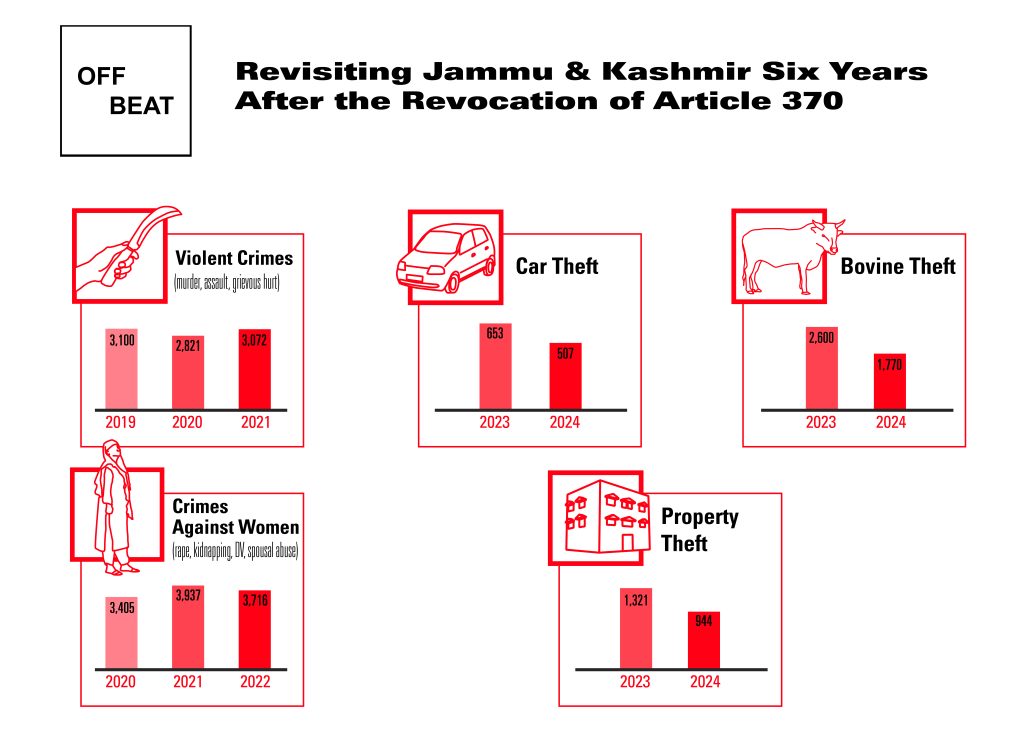

Analysis of violent crime — murder, assault, and grievous hurt — is shown to exhibit a relative stability within the overall rise in reported and collated crime statistics The violent crime case number decreased from 3,100 in 2019 to 2,821 in 2020, then rose slightly to 3,072 in 2021. The plateauing of this trend, especially in its inability to surpass the 2019 baseline, is read by law enforcement as a sign of enhanced policing effectiveness, although it is agreed that deeper issues still exist.

Conversely, perhaps most alarming of the trends evident in the figures is the consistent rise in crimes against women. NCRB statistics point to an increase from 3,405 cases in 2020 to 3,937 cases in 2021, followed by a moderate drop to 3,716 cases in 2022. Rape, kidnapping, domestic violence, and cruelty by the spouse or in-laws form the constituent cases, with the territory reporting the second highest instances of such crimes amongst UTs in 2022. A more introspective analysis of criminal judicial pronouncements demonstrates a parallel consolidation of the institutional response to criminal cases. Convictions increased significantly from 19 in 2020 to 68 in 2022, and arrests increased from 4,548 in 2021 to 6,309 in 2022. Although the increasing number of reported cases could indicate worsening social conditions, authorities also attribute the increased confidence of victims in the justice system to enhanced reporting processes — such as gender sensitization training, the zero First Information Report, and better access to police services. On the other hand, activists and experts argue that the numbers simply represent ongoing societal pathologies, such as deep-seated patriarchal attitudes and the absence of proper social support mechanisms for victims.

More recent statistics from 2024 show a significant drop in many categories of non-violent crime. NDPS (Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances) Act cases totaled 476. Theft of property (excluding motor vehicles) fell to 944 from 1,321 in 2023, motor vehicle theft dropped to 507 from 653, and bovine smuggling cases came down substantially to 1,770 from 2,600. Official sources credit these gains with specific interventions, such as enhanced patrolling, release of state-of-the-art surveillance technology, and intelligence-based operations against criminal gangs.

Mr. Wahid attributes the rise in reported crimes to a paradox of increased state dependency. He argues that the abrogation of Article 370 systematically removed most avenues of local self-sustenance, making the state apparatus the primary recourse for citizens. Consequently, reporting crimes to the police has become one of the few available options.

He contrasts this with the pre-2019 era, when police forces were predominantly engaged in counter-insurgency operations and were seldom viewed as a source of public assistance. At that time, the insurgency movement itself acted as a social deterrent, and communities often resolved local disputes—whether social or violent—through internal mechanisms. Now, with the decline in insurgency in the Kashmir Valley, the police role has shifted toward conventional law and order. This, coupled with active public outreach programs, has repositioned the police as a more accessible, if not the only, institution for redressal, thereby explaining the surge in formal crime reporting.

Dr. Ejaz Ayoub draws a direct correlation between the economic situation and crime, stating: “Yes, there is a clear correlation; economic hardship creates an environment where individuals, particularly youth, may resort to crime as a means to cope with financial instability and a lack of opportunities.” Overall, the criminal landscape of Jammu and Kashmir is a complicated and nuanced one, with overall increased registration over the long term, a stable violent crime rate, a disturbing trend of increasing gender-based violence, and recent success in policing certain non-violent crimes. It would appear that crime trends are subject to an interaction of social forces, reporting efficiencies, and changing law enforcement approaches.

VII. Expert Testimony: A Ground-Level Diagnosis

The insights from economists and analysts provide a cohesive diagnosis of the situation. Dr. Ayoub summarizes the fundamental shift in governance: “The most significant change is the complete disregard for regional economic priorities, with a shift toward managing the region through the lens of political and security imperatives, often at the cost of local needs.” He identifies a clear loss in “the political disenfranchisement from the revocation of Article 370, which undermined local autonomy without delivering visible economic benefits or transformative growth.”

A boy is seen wading through a flooded pathway in Kashmir. // Photo credit: Author

On the critical issue of data and trust, Dr. Ayoub is skeptical of official narratives. He advises that while “macroeconomic reports from the RBI and NITI Aayog give a fair picture […] figures on investment and industrial growth should be treated with caution as they often don’t align with reality.” He distinguishes between economic signal and noise: “The declining share of national GDP, stagnating incomes, and rising debt are the signal of an underlying economic crisis. The noise is the announcements of large investments that fail to materialize on the ground.” This sentiment is echoed in his assessment of institutional trust, which he says “has decreased, with mistrust particularly evident in the police and judiciary, which are now seen as extensions of the state apparatus rather than impartial public services.”

His proposed roadmap for repair is clear and demands immediate political action: “For people to feel a change at home, the Union government must take three actions this year: restore statehood, reinstate land and job ownership rights, and re-populate the bureaucracy with local administrative officers.”

VIII. International Repercussions and Conclusion

Internationally, the revocation of Article 370 precipitated a significant reconfiguration of geopolitical discourse on Kashmir. It triggered vigorous diplomatic responses, particularly from Pakistan and China, which attempted to internationalize the issue at the United Nations Security Council, albeit unsuccessfully (IJRPR, 2024, p. 1167). While the Indian government has managed the diplomatic fallout, the abrogation has undoubtedly strained regional relations and refocused international attention on the Kashmir dispute (IJRPR, 2024, p. 1168).

The revocation of Article 370 has ultimately shown to be a deeply transformative event whose multifarious consequences — constitutional, political, economic, and social — are still unfolding. While framed by the state as a necessary step for integration and development, empirical evidence and scholarly critique point to a reality marked by political alienation, socioeconomic challenges, and ongoing geopolitical tensions. The restoration of statehood, promised by the central government and urged by the Supreme Court, remains pending, with the recent monsoon session of Parliament concluding without any legislative action. The gap between the promise of “One Nation, One Constitution” and the on-ground reality of stagnating investment, high unemployment, a fragile political landscape, and enduring security concerns makes the situation in Jammu and Kashmir a critical and unresolved subject for ongoing academic and policy-oriented debate. For the people of Jammu and Kashmir, it is reality suspended in uncertainty.