Years On, Sumy Struggles with Russian Bombardment

SUMY — Throughout 2025, much coverage of the Ukrainian battlefield has focused on the country’s east, where Russia has pushed ever closer to the embattled city of Pokrovsk. This titanic contest for the Donbas has unsurprisingly sapped attention from elsewhere on the frontlines.

Far to the north, however, another battle is unfolding — one that could see another Ukrainian city subjected to the same fate as Kherson, where Russian drones hunt civilians in what is often referred to as a ‘human safari.’

[Editor’s note: OffBeat Research last reported on Sumy Oblast in January 2025, where reporter Dylan Burns visited towns near the Russian border subjected to artillery and aerial bombardment. Since then, the situation has evolved in line with the broader embrace of drone warfare, affording only increased danger to the residents who have remained.]

With a population of approximately 200,000, Sumy sits on the northeastern gateway of Ukraine around 20 miles (32 km) from the Russian border. Partly encircled by Russian forces in the opening weeks of the 2022 invasion, it was spared direct combat for the next three years, as Moscow shifted its focus to Donbas. That changed in early 2025.

After pushing Ukrainian forces out of a cross-border incursion into Kursk oblast, Putin claimed that Russian troops had themselves drove across the border, seeking to occupy northern Sumy as both retribution and as a ‘buffer zone.’ Capturing a string of villages, Russian forces currently sit around 12 miles (20km) north of Sumy city itself.

This positioning has allowed them to unleash airborne terror of a kind usually reserved for the frontline. Drone strikes on Sumy were bad at the start of the year, but have become near-constant in recent months, with visible destruction that surpasses anything seen outside the worst-hit districts of other cities. Russia has made extensive use of its ‘Italmas’ drone there, using it to strike the city even in daylight hours. One viral video taken in late July shows one of these drones overflying a wedding in broad daylight.

“It’s gotten harder in recent months,” says Yuriy Danko, the vice-rector of Sumy’s National Agrarian University (SNAU). Danko himself was the author of the viral video, which he took while attending a friend’s wedding. “It was never that quiet here, but [the Russians] are making it louder now,” he says.

The statistics bear this out. Recent Russian strikes have hit both power and rail infrastructure in the city and its environs, part of an ongoing campaign to knock out critical infrastructure ahead of the winter. Civilian sites, meanwhile, are struck seemingly at random. One drone that hit a crossroads on October 21 injured nine civilians. Strikes on the premises of SNAU, a handsome and modern campus that sprawls across the city’s southwest, have likewise become increasingly commonplace.

Danko himself had a close call in one of the strikes.

“There was one [drone] that hit just outside, when me and the rector were in this exact room. We could feel the blast. A small difference in trajectory, and I wouldn’t be here right now,” he says.

In many ways, Sumy is an obvious target for Russian terror. A major city lying near the border, it is a low-hanging fruit, well within range of nearly everything in the Russian arsenal. Strikes have been rare, however, until late last year, leading some locals to conclude that the rationale is now as much political as strategic: punishing the nearest Ukrainian city for the Ukrainian armed forces’ incursion into Russia’s Kursk oblast in August 2024.

Katya Frolova, a Sumy native, splits her time between her job in Dubai and visits to her hometown to care for her elderly grandfather. She says there was a clear uptick in bombing following the Kursk operation.

“In 2023 and earlier in 2024, things weren’t great, but the attacks were very much concentrated on the border,” Frolova says. “And then Sumy put itself back on the map, so to speak, with the [Kursk] incursion. So now we’ve got not only the regular strikes, but Sumy is even being used as a testing ground for these new [Russian] drones.”

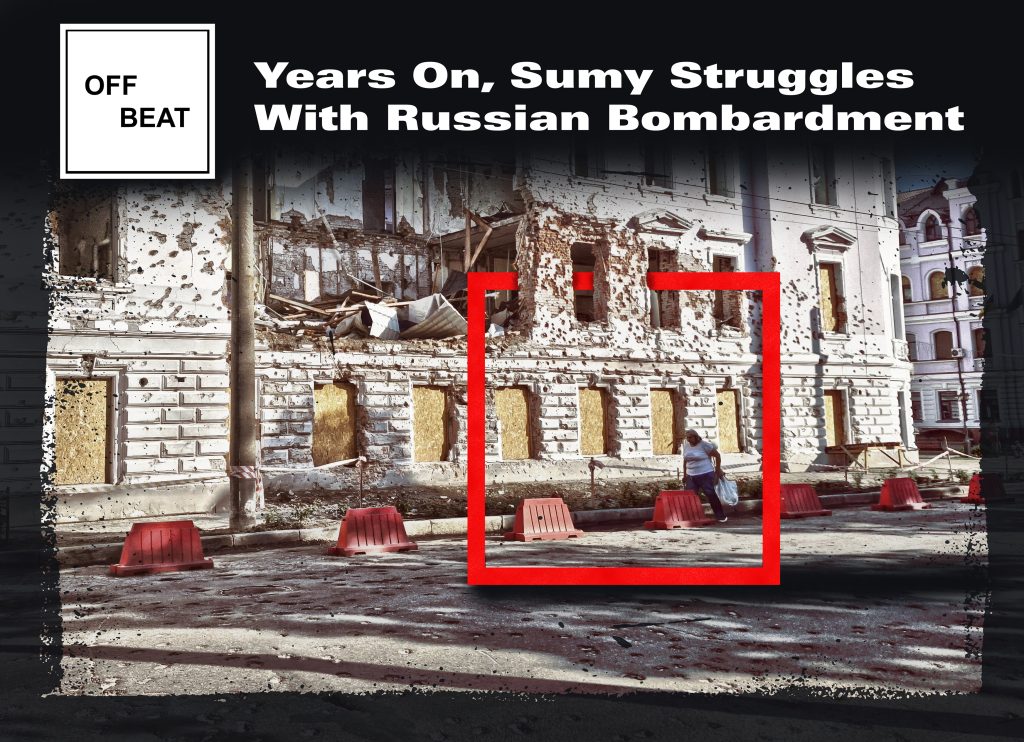

The facade of Sumy’s Regional Administration Center shows that most windows have been either boarded up or blown out by recent drone strikes. // Photo credit: Neil Hauer

A short walk around Sumy’s city center is enough to see the results of this. The broad streets are pocked with shrapnel, the only remnants of most attacks: Ukrainian repair crews have become exceedingly efficient at quickly erasing the worst effects of bombardments. Some buildings, having suffered more recent attacks, bear more obvious scars. One such building is Sumy’s regional administration center, whose facade is pocked with perhaps a half-dozen blown out windows, their concrete frames blackened from drone strikes only two days earlier.

And then there are the worst cases. On Soborna Street, a small thoroughfare in a heavily populated area, one building stands open to the elements, with a two-story hole torn into its facade. Exposed brick and shattered timber face the street, bracketed by a roof that is half gone.

A destroyed building on Sumy’s Soborna Street. // Photo credit: Neil Hauer

This is the result of one of the deadliest weapons in the Russian arsenal: The KAB series of ‘glide bombs.’ Launched from Russian jets dozens of kilometers away, the massive bombs can weigh up to three tons and have little counter.

“These are the worst we see,” says Frolova, surveying the half-ruined building. “Being right near the border exposes us to glide bombs. Shahed [drones] are bad enough, but these can tear a building apart,” she says.

Despite conditions in the city itself, Sumy’s countryside has been one of the bright spots for Ukraine’s armed forces in recent months: it is one of the rare areas where Ukrainian soldiers have reclaimed land, rather than ceding it. With Russia pulling manpower from the Sumy front to reinforce its push on Pokrovsk, Ukrainian troops managed on August 10 to recapture the village of Bezsalivka, a border town some 9 miles (15 km) from Bilopillya and around 31 miles (50km) northwest of Sumy city. Additional reports in October alleged that Russian troops were being pushed further back in the village of Oleksiivka — a key node at the forwardmost edge of Moscow’s main spearhead towards the city.

But while Russian forces may be on the back foot on the frontline, their capacity to strike Sumy itself is unlikely to be affected.

The worsening tempo of strikes seems to attest to this, including the growing phenomenon of daytime attacks which were earlier a rarity in Russia’s aerial campaign against Ukraine’s cities. This point is dramatically underscored by a growing series of videos showing such attacks — most recently on October 22, in a cell phone video that shows a Shahed drone slamming into a Sumy street in broad daylight.

“Just yesterday there was another daytime attack,” says Frolova. “They hit one of the power substations around here, so there was no electricity for most of the day. I could hear drones hanging in the air over the city, too, that constant buzzing that never goes away,” she says.

Her reference to the power grid is an ominous one. As winter approaches, Russia has again upped its assault on Ukraine’s electric and heating grid, seeking to force blackouts.

While Ukraine has grown experienced in mitigating these attacks over the past three years, the sheer scale of Russia’s campaign this year is likely to cause serious problems. The past month has been a dark portent, with Russia knocking out more than half of Ukraine’s gas production. A recent Ukrainian publication warned of Russia attempting to ‘methodically destroy’ Ukraine’s energy system in its entirety, with a particular focus on the Sumy and Chernihiv regions. As early as October, well in advance of winter, emergency power cuts had already been (temporarily) imposed on most of the country.

“People forget about Sumy because it’s not one of the main areas of the war now,” says Danko, the vice rector. “But it is still important. It is one of the biggest cities in Ukraine near the border. There are almost a quarter of a million people here that are under threat from Russian drones,” he says.

This pattern of relentless, largely random drone attacks on frontline cities like Sumy has inevitably led to increased waves of displacement, as residents balance daily life with the constantly disruptive threat of aerial bombardment.

“There is a pattern of people going to specific places,” says Kseniia Bliumska-Danko, a Sumy resident who works in marketing. “People from the east, they go to Kharkiv or Sumy. People from Sumy go to Kyiv. People in Kyiv go abroad,” she explains.

“But people will not do this forever,” Bliumska-Danko adds. “We have many people here who have already come from Luhansk or Donetsk. If they are forced to leave Sumy, will they really just go to Kyiv and set up their lives again where they can still be bombed? Many of them will probably leave the country entirely.”

That fate is still far from certain. Sumy is struggling, though it still resembles Kharkiv more than Kherson. But with a difficult winter approaching, the next wave of displacement could be closer than many realize.