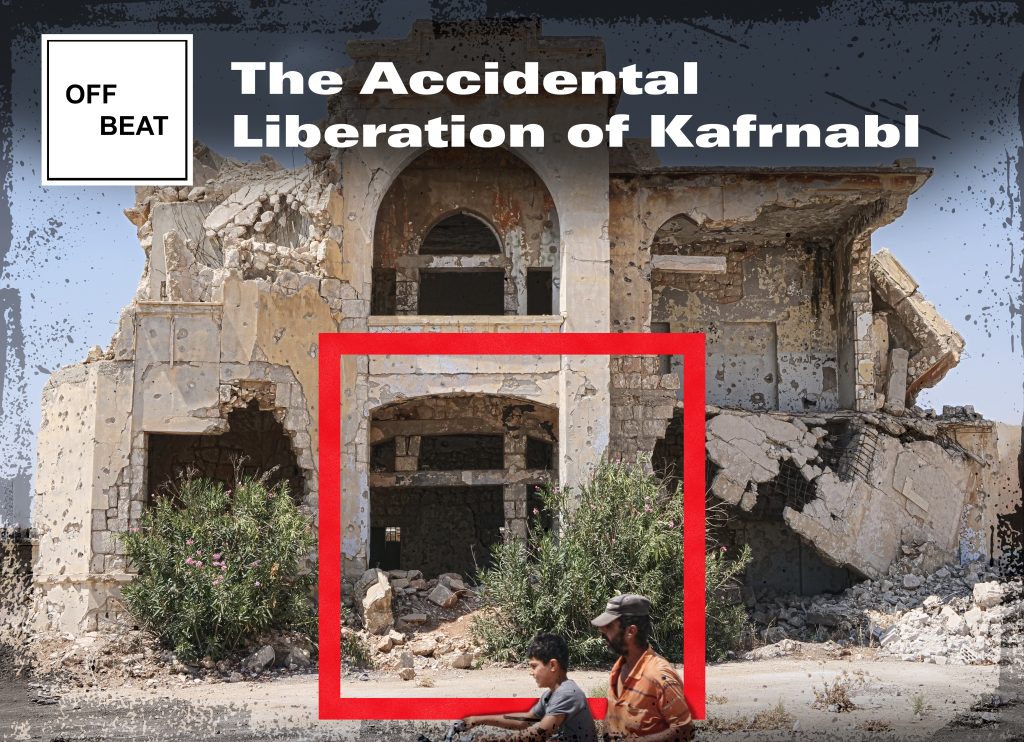

The Accidental Liberation of Kafrnabl

KAFRNABL — I meet Ahed outside some gutted and long-abandoned buildings on Kafrnabl’s main street.

It is more than an hour’s ride on his motorcycle to this town from his home in Armanaz, where his family has lived since the regime expelled them from their houses more than five years ago. Together, we make our way through the town’s streets to his friend Mahmoud’s house.

Most of Kafrnabl is destroyed; those buildings not fully uninhabitable are nonetheless severely damaged. The town’s physical condition is not as bad as many others throughout Jabal Zawiyah, the hilly farming region of southern Idlib. Like everywhere else, however, it has sat empty of every inhabitant since the regime captured the area in early 2020. What remained after the regime’s entry — refrigerators, small appliances, copper wiring — was subsequently stripped bare, looted and pillaged by thousands of regime soldiers and militiamen.

Still, the fall of Assad eight months ago has sparked a return of life to what was once the heart of Syria’s revolution.

Anyone who has followed the war at some point in the past 13 years will have known Kafrnabl. The town became famous early on in the war as a hub of revolutionary art and culture, particularly for its satirical protest banners and graffiti. Throughout the war, the town and its residents remained staunchly committed to non-violent protests against all authoritarian actors: the Assad regime, Russia, Iran, ISIS, and Hayat Tahrir ash-Sham.

Ahed was one of these early revolutionaries. A police offer serving in the Aleppo International Airport, he used his position to help rebel groups in Idlib smuggle laptops and electronics into the country. His friend, Mahmoud, was a successful farmer before the war, growing mostly apples and plums; his Facebook page is still filled with pictures and videos of his old orchard.

Mahmoud has already made significant progress rebuilding his home. Clean, black-speckled white tiles cover the floor, and a fresh coat of paint coats the walls of his empty rooms. But he’s most proud of his newly replanted garden, which marks the first step towards reclaiming his farmland which was desecrated by years of looting and neglect.

Mahmoud’s newly planted garden. // Photo credit: Gregory Waters

We soon move to Mahmoud’s basement, the only reprieve from the summer heat. Over a lunch of fresh-grown cucumbers and plums, Mahmoud and Ahed tell me the story of their town’s revolution.

Jabal Zawiya Under Attack

The first major demonstration in the town was held on April 1, 2011. Dubbed the “Friday of Martyrdom”, hundreds of people took to the streets in support of protestors who had been killed across the country by security forces over the previous weeks. From then on, protests were a weekly occurrence, continuing for nearly 10 years until the regime captured the town. Among those organizing and documenting the first protests was a then-unknown Raed Fares, a man who would go on to become the face of Idlib’s non-violent movement.

Kafrnabl’s first protest, circa April 2011.

Regime raids began later in April, but it was not until late June when the situation truly deteriorated. On June 5, civilians and nascent armed groups stormed the Jisr Shughur Military Intelligence Directorate headquarters, killing more than 100 intelligence officers and briefly expelling security forces from the city. This attack was the result of steady escalations and abuses by security forces which had fractured a fragile truce in the region.

Following the attack, which constituted the largest loss of life for regime forces up until that point, massive military reinforcements were sent to Idlib in order to support the raids and operations of regime mukhabarat and police. In early July, a special forces battalion belonging to the 14th Division’s 556th Regiment established a headquarters in Kafrnabl’s high school and set up a series of checkpoints at all major intersections.

A convoy of BMPs arrives in Kafrnabl on July 4, 2011.

In a span of 48 hours, the city was transformed. Tanks and BMPs showed up overnight, and armed checkpoints were established across the town. Hundreds of soldiers from the Air Force Intelligence Directorate, Special Forces, and 3rd Division now occupied the town. “They came before any of us were holding weapons,” says Mahmoud, “and they arrived shooting bullets in the air, trying to intimidate us.”

A regime convoy of 18 troop transport trucks and a Shilka arrive in the town in the first week of July 2011. A tank from a unit that arrived earlier can be seen as well.

Like Ahed, many men in Idlib sought careers in the police over the previous decade, driven by the governorate’s poor economy and lack of jobs. Serving in the police also meant being able to return home on the weekend, something soldiers confined to their bases were unable to do. Ingratiation into the regime’s domestic policing apparatus also afforded police officers the ability to serve under Sunni commanders, rather than in the Alawite-dominated army.

These regular drives between Idlib and Aleppo gave Ahed a clear view of the regime’s escalation. “By late 2011, whenever I would travel I would see huge convoys of military vehicles moving into Idlib,” he recalls, “Never less than 200 vehicles each time.”

As the regime initiated its push of major military reinforcements into Idlib, towns began forming self-defense forces. The most famous of these were the Free Officers Movement, established on June 9 by the defected Lieutenant Colonel Hussein Harmoush, himself a native of Jabal Zawiyah; and the Free Syrian Army, established in a refugee camp on the Turkey-Idlib border on July 29 by the defected Colonel Riad al-Assad.

The new military deployments and operations immediately following the June battle of Jisr Shoughur put significant pressure on the armed opposition that had just begun to form in Idlib. Successful attacks against regime forces were rare, and mostly focused in Jabal Zawiyah. On August 17, members of the Free Officers Movement released a statement announcing the formation of “deterrence groups” which would actively protect “safe” villages from regime raids by targeting attacking regime forces. In the announcement, the officers claimed to have conducted their first operations against security forces who were attempting to raid villages in Jabal Zawiyah that morning.

In Kafrnabl, regime members bringing supplies to the new positions would shoot in the air at first. After a while, they began shooting at people in the streets. One man riding a motorcycle was shot in the leg and bled out. Mahmoud was shot in the arm. Once, a BTR drove down the main street and shot at people in the bakery. As these kinds of attacks became more intense, locals started to defend themselves and outright skirmishes began.

“Before July, our focus was just on organizing protests,” recall Ahed and Mahmoud as we sit in Mahmoud’s newly rebuilt basement. “But after the military arrived our thinking shifted, we started talking about making mines and IEDs and how to defend ourselves.”

Kafrnabl Arms Itself

As the regime intensified its crackdown across the country it began to utilize the police as well. As more police units were ordered to fire on unarmed protestors, police officers – many of them Sunni – began defecting in droves. These police defections, along with those of army officers, helped bolster the new armed groups in Jabal Zawiyah in general, but particularly in Kafrnabl, where many men had joined the police.

The Kafrnabl revolutionaries were still dominated by civilians, however. Many of these men were university-educated, but the one common factor between all of the civilians-turned-fighters was unemployment. As military defectors joined this group, they were quickly able to put their education and military expertise to use.

Armed only with small arms and Molotov cocktails, the defenders in Kafrnabl needed something to deter the armored vehicles that patrolled their streets and led the raids against their homes. “It was a mutual effort,” says Mahmoud, “one person had the explosives knowledge, others would bring the materiel, someone else would make the detonators.” It was Jihad Zatour who built the bombs, using his experiences serving at a military explosive manufacturing plant before his defection. He worked closely with Hassan Khatib, a high school graduate with a knack for electrical engineering who quickly developed innovative detonators. Zatour would go on to become the military commander of Kafrnabl’s armed faction, before he was assassinated with an IED in 2014.

Jihad Zatour, pictured some time before his death in 2014.

The other weapons and ammunition were crowdsourced from a variety of sources. Sometimes defectors were able to bring their weapons with them; other times, the locals would buy guns from corrupt army officers, often using money donated by local businessmen. Syrian diaspora networks in Saudi Arabia also helped pay for some weapons smuggling into the town.

“The mines were a response to the regime’s violations,” says Ahed, who himself defected in February 2012. According to Ahed, the town’s opposition leaders repeatedly told the regime officers, “If you don’t want to die, just leave your weapons and leave the area.” When they refused, they asked the officers to at least stop shooting at civilians. As violations didn’t stop, then the revolutionaries began to attack.

Slowly, the IED campaign helped disrupt regime movement in the city. Explosives were placed on the main road, hidden under trash bags or rocks, and usually detonated using a radio frequency transmitter, like a car key fob. But tanks remained out of the reach of their DIY explosives.

From here on, skirmishes gradually increased across the city. In February 2012, the regime launched a massive military operation across Idlib governorate which left hundreds of civilians dead, often executed in their homes during army raids. In Kafrnabl, the violations also increased throughout the summer of 2012, with rebel actions triggering more violent crackdowns. In one case, per Ahed, after a rebel sniper killed a soldier, the regime embarked on a campaign of random arsons and arrests, targeting local shops and kidnapping many civilians who were were never seen again.

An Accidental Liberation

Despite regime retaliation, the constant skirmishes slowly paid off. The pressure the army was facing across the entire Jabal Zawiyah region had steadily built through the summer of 2012, overextending units and forcing them into increasingly isolated positions and reducing the regime’s freedom of movement. By August in Kafrnabl, the regime had just a special forces battalion and a handful of intelligence units spread between two main bases and only a handful of small checkpoints, facing off against around 200 armed fighters.

On August 6, the battle for liberation began. However, it was never meant to be a battle. Over the previous days, tensions in the town had drastically increased, so much so that the regime withdrew its remaining checkpoints back to the two bases. Unbeknownst to the opposition fighters, the regime officers were planning to launch a large operation against the entire town using their now consolidated units.

At the same time, the rebel fighters had acquired a 14.5mm heavy machine gun – their first heavy weapon – and were eager to test it out. According to Ahed and Mahmoud, the fighters decided to fire on the main regime base in the high school as a test. But the regime responded harshly with its own intense fire. More fighters mobilized and joined in, with the skirmish quickly escalating into street fighting. Meanwhile, the regime deployed its heavy armor from inside the high school. Bereft of any anti-armor weapons, fighters were forced to climb atop regime tanks and throw molotovs into the hatches to take them out.

The fighting didn’t ebb for the next 48 hours. Suddenly, what had been a weapons test had turned into a potential turning point not just for Kafrnabl but for all of Jabal Zawiyah. On August 8, the other factions of Jabal Zawiya, realizing what was at stake, mobilized their own forces. More than 2,000 opposition fighters arrived, mostly from Liwa Suqour al-Sham and the Syrian Martyrs Brigade.

The severity of the regime’s tenuous position was clear when the air force began bombing the town in standoff strikes, marking the first use of jets to bomb the governorate. After two more days of street battles, the town was liberated. Dozens of special forces soldiers were killed in the battle, including a colonel, and another 37 were captured. Among the prisoners was the commander of the Kafrnabl garrison and head of the town’s special forces battalion, Colonel Mundhir Saloum.

The fall of the Kafrnabl garrison created a cascading effect. Regime forces in the vicinity quickly withdrew to Maarat al-Numan, the strategic city straddling the Hama-Idlib highway. The opposition was now on the steps of Jabal Zawiyah’s largest city, and had finally ended the raids and killings in Kafrnabl and its neighboring towns.

Memorializing the Revolution

The surrender of the last soldiers in Kafr Nabl was captured in a short three-minute video, shared in August 2012, with the men seen being escorted through a crowd of celebrating locals. Suddenly, out of the crowd emerges the bloodied face of Raed Fares, his camera slung around his chest. Exhausted, he turns to the man filming and emphatically announces the liberation of his city.

For the next six years Raed was the face of not just Kafrnabl’s revolution, but Idlib’s secular democratic movement as a whole. After Kafrnabl’s liberation, Raed formed a group of youth dedicated to organizing aid basket deliveries across the surrounding area. As a media activist, he led non-stop demonstrations against the regime and against radical Islamist groups; led local protests calling for international protection; and fostered support for martyred civilians and fighters. The town’s fighters would quickly form their own Free Syrian Army faction under the command of the defected Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Fares Bayoush. Like Raed, Liwa Fursan al-Haq and Fares Bayoush would maintain the original ideals of the revolution, despite the growing complexity of the revolution’s internal politics. Eventually, as the Islamist armed groups gained power in Idlib, Fares Bayoush himself was exiled to Turkey.

Years later, in 2018, Raed was assassinated by thus-unidentified gunmen who likely belonged to Hayat Tahrir Ash-Sham (HTS), which governed Kafrnabl at the time of his assassination and which currently governs the entirety of Syria today. Raed’s murder marked a low point for revolutionary activists, a period when armed groups including HTS violently suppressed secular activists and critics. Raed’s dedication to the revolution’s original ideals, however, has left behind a legacy synonymous with the name of Kafrnabl, one which can never be destroyed.

Ahed’s family home now stands in ruins, too costly for him to rebuild. // Photo credit: Gregory Waters

Raed Fares, Jihad Zatour, and hundreds of other activists and fighters from the city never saw the fall of the regime, but their sacrifices helped ensure the town would never be erased. Today Raed’s friends and family – like his cousin Ahed – have begun returning to their city once more. 500 families have now left the tent camps along the Turkish border, though they still suffer from a lack of water, electricity, and bread amid the ruins of their old homes. Still, these survivors are slowly rebuilding Kafr Nabl with their own hands and money. In doing so, they are cementing the region’s history and its unrelenting demand for freedom, and closing the chapter on their revolution.